For the past two years, everybody has been talking about the invasion of small-town Ontario by refugees from the city. The traffic in town is now just like Toronto; in fact, it is a little bit worse. In Toronto, you have a homogeneous traffic stream of reasonably skilled drivers hurtling toward their destination like a school of fish or a flock of blackbirds. Miraculously, they don’t bump into each other all that often.

But out here in the country you have a dangerous mix of blackbirds and pelicans. There’s Mike and Vern leaving their morning driveshed coffee club meeting in their GMC pickup, meandering up the recently paved Tenth Concession and trying to recall who settled what farm 200 years ago. Behind them is a dot.com trendoid fighter pilot in an Infiniti who thinks he can get around them on Short’s Hill. This is a bad combination and frequently ends in tears at any season of the year, but winter jacks up the risk factor by a multiple of five.

The Tenth was never a great road to do anything risky. Smart cyclists avoid it. Before the rebuild it was narrow, hilly, full of potholes, and if you slipped off the road you would need a tow truck. So most people avoided the route altogether or learned to drive carefully. Highway engineers have made it far less forgiving. The road is now narrow, hilly and extremely smooth. The ditches fall away at such a steep angle you are more likely to need an ambulance before you think about a tow truck.

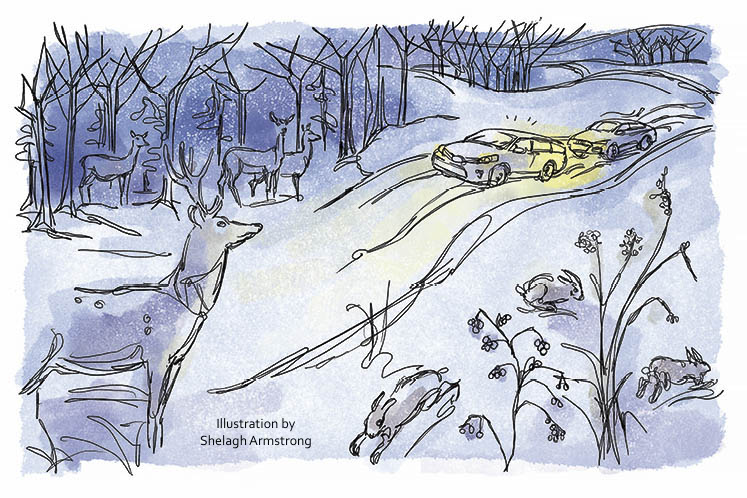

Several years ago, my younger daughter was learning to drive when the police issued a stern warning about the need for caution during deer season. Nearly 30 incidents had been reported on area highways in the past month. I mentioned this to my young policeman friend and he told me, “Dan, that public service warning was actually aimed at the police. We smashed up something like ten cruisers hitting deer this fall.” My daughter helped bring the statistics back to normal.

On one of her first excursions by herself in the dark, she smacked into a deer and smashed the headlight on our Toyota van. The deer escaped with minor injuries and I replaced the headlight with a unit from a wrecker for 20 bucks. But her driving habits changed noticeably. On dark nights, she hunches over the wheel like a bird of prey, scanning the road for the slightest movement in the ditches.

Everybody, from the novice driver to the recently arrived urbanite to the highly trained young police cadet, all go through the same steep learning curve. In the first heavy snowstorm of one recent December, my daughter was wending her way carefully down River Road when headlights zoomed up behind her and began flashing at her to get out of the way. She pulled over and an Audi zipped by. A few minutes later she saw flashing lights ahead and pulled up to find the Audi with a deer lying over its hood. The driver was standing in the middle of the road yelling into her cellphone. She wasn’t interested in any offer of assistance.

In the Great Blow of 1975, I was working in the family restaurant when a group of 16 people appeared at the door looking for shelter. They had been waiting in a cluster at the gas station when the snowplow driver announced he would make one last run to the next town seven miles away. Just before he pulled out, a Cadillac came sailing down from the west and promptly disappeared into a four-foot snowbank across the road. They got the poor fellow out with shovels, but he had to spend the next three days sleeping on the floor of our restaurant surrounded by eyewitnesses to his driving error. I’m sure he still winces when he recalls that experience. I know it changed my own driving habits.

One of the reasons for our population surge is the realization that technology allows many of us to work from anywhere we choose. It’s the same technology that allows us to stay home in front of the fire when the winds blow and the snow flies.